A US president’s first foreign trip is usually towed by tradition: a ceremonial stop at North American neighbours to reaffirm the close cross-border ties on the continent. President Biden however – though in part honouring convention with “virtual” bilateral meetings with the leaders of Canada and Mexico earlier this year – is marking his maiden journey with an excursion to Europe this month, visiting the UK to attend the G7 summit before travelling to Brussels for NATO and EU meetings.

And Biden’s break with tradition is with good reason. Aside from repairing relations with the Brussels-based organisations that his predecessor thoroughly strained, the president’s inaugural overseas outing will seek to underscore the US’ commitment to “strengthen democracy” and “address mutual foreign policy concerns,” a statement from the White House reads.

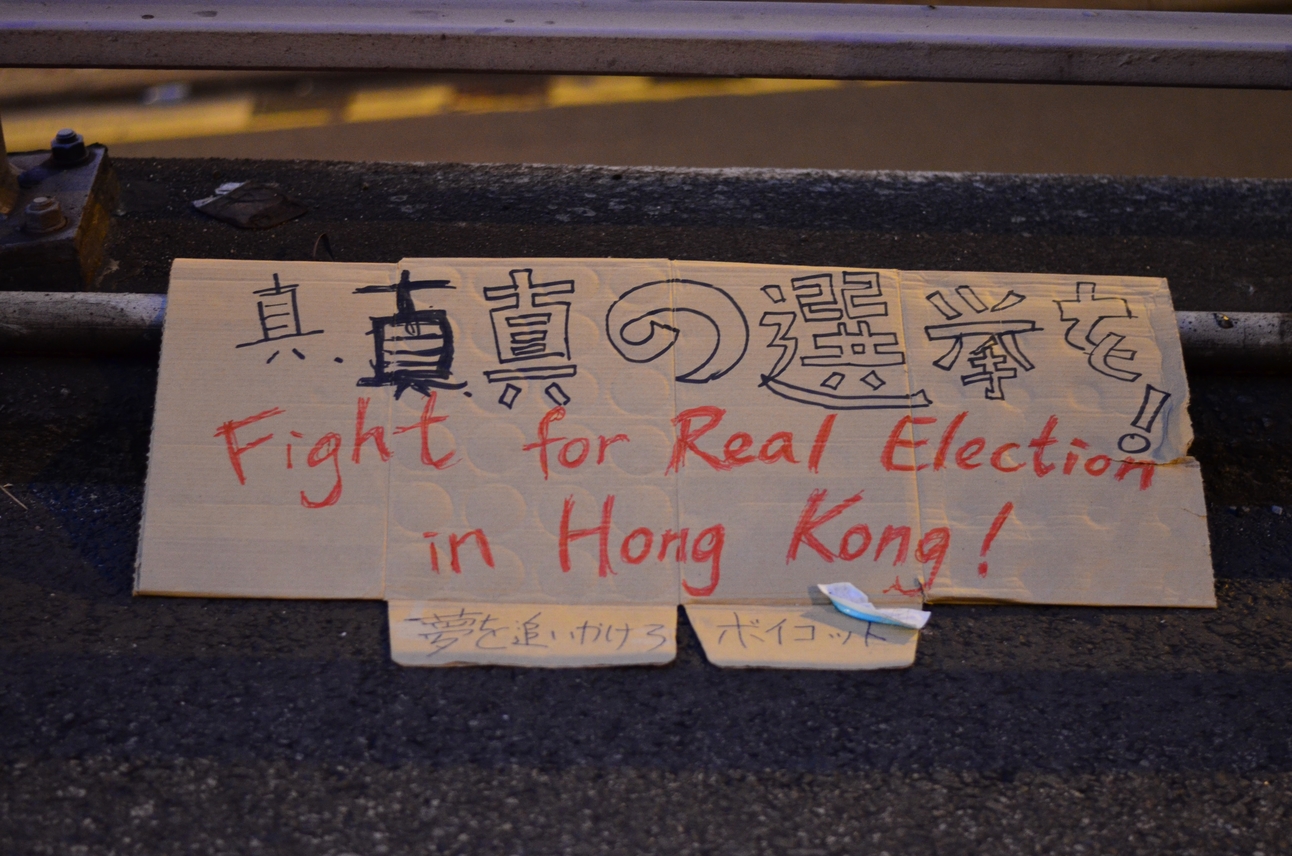

One such mutual concern should be China’s mounting repression in Hong Kong. Days before Biden is due in Brussels, Hongkongers will be marking two years since popular, largely peaceful protests erupted in opposition to Beijing’s attempts to erode freedoms in the territory.

Since then, the situation in Hong Kong has steadily worsened. Widespread demonstrations throughout 2019 against plans to introduce extradition to mainland China – which risked exposing Hongkongers to China’s systemic malpractice of unfair trials and detainee abuse – were met by an unprecedented show of police brutality in Hong Kong, including, as Amnesty International has documented, “evidence of torture and other ill-treatment” of protesters in detention.

Though the extradition bill was dropped under the weight of mass demonstrations later that year, the worst was yet to come for Hong Kong. In 2020, Beijing bit back with a vengeance, and imposed the sweeping national security law – criminalising free speech and the right to assembly overnight under the pretext of restoring stability.

The law, which carries punishment of up to life imprisonment, is purposely imprecise in nature and ambiguous in interpretation, criminalising secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces – but failing to express what acts might constitute such an offence. The move led the UK to declare a breach of the internationally recognised Sino-British Joint Declaration that guaranteed the autonomy of the former British colony and the rights of its people under the “one country, two systems” principle enshrined in Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

Under the auspices of the draconian security law, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has moved swiftly to crack down on dissent. In the past year, Hong Kong police have arrested at least 100 people, including 55 pro-democracy activists and politicians in dawn raids. 47 of the opposition figures arrested have since been charged with “subversion”, and face the possibility of life in prison for taking part in popular, unofficial primary elections last year after authorities postponed legislative elections, citing concerns over the pandemic.

And just last week, Hong Kong’s puppet parliament, devoid of any substantial opposition following the mass disqualification, resignation, detention and exile of pro-democracy lawmakers, rubber-stamped the CCP-dictated ‘patriots’ only law.

The bill, first initiated by the Chinese government in March, will drastically diminish democratic representation in the city’s parliament by slashing the share of directly elected seats in the legislature to 22% – down from 50%. The electoral reform will also install a new vetting committee to screen election candidates, with the purpose of weeding out any last remaining “unpatriotic” – read dissenting – voices, cementing Beijing’s control of the governing body in Hong Kong.

The dismantling of democracy and assault on freedoms in Hong Kong has been sinister and systematic – yet has gone largely unpunished by the EU and UK. Whilst officials in both camps have been quick to condemn the catalogue of coercive measures by the communist regime, little has been sought in the way of sanctions on officials complicit in abuses in Hong Kong.

This inaction persists despite Britain and the EU recently adopting Magnitsky-style sanctions regimes designed to target those involved in human rights abuses – and indeed imposing coordinated sanctions under these new mechanisms on Chinese officials accused of perpetrating gross human rights violations against the majority-Muslim Uyghurs in China’s Xinjiang province.

Conversely, the US has pursued a far more aggressive line on Beijing’s litany of repression in Hong Kong. Beginning in the Trump presidency and brought forward by Biden, the US has enacted a series of measures that would impose sanctions on businesses and individuals that are involved in China’s assault on Hong Kong’s autonomy, in response to the passage of the national security law last year.

Washington has also passed legislation restricting the sale of crowd–control weapons, such as tear gas and rubber bullets used by Hong Kong’s police to target protesters, and stripped Hong Kong of its favourable trading terms, threatening the status of the city as a global business hub by subjecting it to the same tariffs and regulations as mainland China – including the extra charges that were placed as part of the ongoing US-China trade war.

More recently, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced sanctions on 24 Chinese and Hong Kong officials in response to the CCP’s sweeping changes to Hong Kong’s electoral system in March. The move, which came ahead of the Biden administration’s first major talks with Beijing, sets a firm tone – amidst the backdrop of penalties imposed by Washington in the past two years – for the US’ engagement with China over Hong Kong.

Though critics have argued that Washington’s confrontational approach over freedoms in Hong Kong is born out of its competitive rivalry with China, the US has demonstrated that decisive action, with the potential to push back on Beijing’s incursions in Hong Kong, is possible.

As the international summits are underway, the UK and the EU, as custodians of the Sino-British Joint Declaration and self-styled champions of human rights, respectively, should look to follow the firm lead of the US on Beijing’s repression in Hong Kong, and impose sanctions on officials complicit in human rights abuses in the last, dying bastion of freedom in communist China.

Political Consultancy

The Whitehouse Communications team are experts in providing public affairs advice and political analysis to a wide range of clients engaging with health and social care providers and policy makers, not only in the United Kingdom, but also across the member states of the European Union and beyond. For more information, please contact our Chair, Chris Whitehouse, at chris.whitehouse@whitehousecomms.com.