Today’s Queens Speech ushers in the biggest shake-up of prison services since Victorian times as governors of six prisons – including HMP Wandsworth, Britain’s largest – are handed new control over budgets and services. At the heart of the reform programme is a commitment to improving skills and education services, following the advice set out by Dame Sally Coates in Unlocking Potential: A review of education in prisons. Currently, 47% of prisoners have no formal qualifications at all on entry to prison, 42% were expelled or permanently excluded from school and 13% report never having had a job. Today’s reforms seek to change this.

However, while the government’s determination to make sure that prisons become “places where lives are changed” is to be welcomed, there are a number of structural challenges that must be acknowledged.

Underdeveloped training opportunities

Between June 1993 and 2015 the prison population in England and Wales more than doubled from 41,800 to over 85,000 prisoners. However, despite increased incarceration level, reoffending rates remain high. Indeed, almost half (47%) of prisoners reoffend within twelve months of release.

This is partly the result of limited access to training and education services. As research by HM Inspectorate of Prisons, Probation and Ofsted has found: “too few (prisoners) experienced a sequenced and focused approach that would enable them to progress to higher level learning in an area that would help them to access further training or employment on release.”

A new approach is needed to ensure that all prisoners are equipped with the basic level of literacy and numeracy required to get onto the job ladder. However, this should not be an end in itself, but rather part of a wider education framework. By offering access to a relevant standard of education and a track towards further qualifications, prisoners can be incentivised to fulfil their potential and secure employment upon their release.

Education should not be limited to class room learning, but must incorporate a broad curriculum to encourage and sustain aspiration. This may include vocational training, access to careers guidance services and, where appropriate, community work programmes or apprenticeships.

Few opportunities for specialists

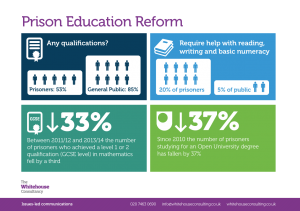

In 2014, Ofsted reported that education levels across the British prison system were inadequate and suggested that “very few prisoners are getting the opportunity to develop the skills and behaviours they need for work.” Between 2011/12 and 2013/14 the number of prisoners achieving a level 1 or 2 qualification in Mathematics fell by a third, and since 2010 the number of prisoners studying for an Open University degree has dropped by 37%: clearly indicating the need for substantive reform.

Less tangible, but no less important, poor education services represent a missed opportunity for human improvement and ensuring that the justice system is a conduit to a better society. Too often prisons fail to equip offenders with the tools needed to build fulfilling lives upon their release.

A new perspective is required to engage organisations and their experiences, and create a more flexible prison system. This is a unique opportunity for providers to exert influence and shape the education and training agenda.

Public skepticism

Research carried out by the Whitehouse Consultancy in association with ComRes found that nearly three quarters of Britons (72 percent) agree increased investment in prison education and training is worthwhile if crime rates fall in the long term, but more than half (55 percent) believe rehabilitation is ineffective in preventing repeat offences.

Meanwhile, nearly two-thirds of Britons (62 percent) agreed that prisoners should be able to access training and education. However, just half of respondents (48 percent) agreed prisoners should be able to study for advance (university level) qualifications, suggesting a willingness to cap opportunities for training and education in prisons.

Finally, half of Britons (51 percent) agreed that prison should be focused on punishment rather than rehabilitation; although a similar proportion (49 percent) agreed offering prisoners training and education reduces the deterrent from committing crimes.

These findings illustrate a key challenge for education and training providers: demonstrating to the public that their methods work and will have a positive impact on reducing reoffending rates.

Opportunities

Although the challenges outlined above are great, the government’s reform agenda presents substantive opportunities for new and established providers. For example, Unlocking Potential proposes that “education in prison should give individuals the skills they need to unlock their potential, gain employment, and become assets to their communities.” This will only be achieved through cooperation between the public, private and third sectors, and by engaging experts in shaping the future of Britain’s prisons.

Recognising this, the Coates review suggests that, “engagement with a full range of local partners” take place to help establish a “consistent and shared vision of the education needs of the prison and of how provision supports this.” The review also proposes that “market engagement activity” be undertaken to ensure that “Governors have the broadest possible opportunities to engage with a range of providers of education services to reach a judgement on which best meets the needs of prison learners.”